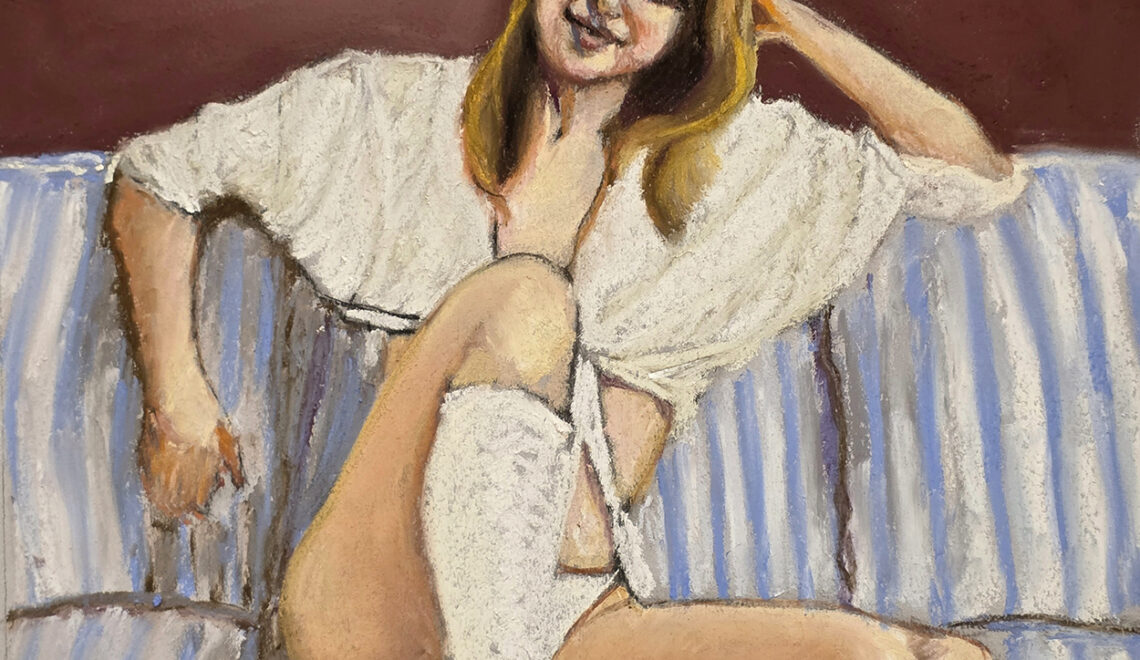

In this trois crayons drawing, André Romijn initiates a refined dialogue with the eighteenth-century sensibility of Jean-Baptiste Huet. The work breathes the atmosphere of the pastoral genre—idyllic, intimate, and suffused with a gentle theatrical melancholy—yet it does so with a contemporary command of light and texture.

What stands out immediately is Romijn’s mastery of the medium. The three chalk colours (black, red, and white) are not deployed as mere displays of virtuosity, but as tools to construct a subtle psychological landscape. The young woman’s body, shaped by warm red tones and soft modelling, forms the radiant centre of the composition. Her posture—slightly leaning forward, one hand thoughtfully at her chin, the other tenderly extended towards the goats—captures a moment of quiet contemplation. She is not merely a shepherdess but a figure engaged in an introspective dialogue with her surroundings.

The animals are rendered with remarkable sympathy and character. In their expressions—particularly the goat stretching its nose toward the woman’s hand—there emerges a moment of connection that borders on the human. Romijn echoes Huet’s pastoral charm but tempers it, turning the scene into something calmer and more meditative. The animals are not decorative elements; like the woman, they are carriers of stillness and reciprocity.

The drapery deserves special attention. In less disciplined hands, drapery in trois crayons can easily become static, yet here it feels light, almost breathing. The cloth falls in wide, soft folds that, through black chalk lines and white highlights, acquire a convincing sense of volume. The contrast between the deep shadow behind the woman and the velvety texture of the garment creates a delicate interplay of mass and weightlessness.

Compositionally, the work is both clear and compelling. The diagonal formed by the woman’s body—from her head down to her extended hand—acts as a visual bridge between the human and the animal world. Huet’s legacy—pastoral charm and Rococo elegance—is unmistakable, but Romijn shifts the emphasis away from decorative appeal and toward a quieter, more introspective register. It is a transposition of eighteenth-century refinement into a contemporary sensibility.

Ultimately, the strength of this drawing lies in its emotional subtlety. The scene does not indulge in nostalgia or sweetness; instead, it conveys a moment of gentle human presence, captured through a technique that balances simplicity with sophistication. Romijn proves himself not only a skilled craftsman but an artist capable of letting the sensibilities of the past resonate within a modern gaze.